Wolffish: driven to near extinction by fishing, two obscure fish test the will of Canadians to preserve indigenous species versus commercial interests

(As government scientists offer disinformation to the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans in their request to exempt fishermen from legal prohibitions against causing further harm to the severely “threatened” northern and spotted wolffish.)

by Debbie MacKenzie, August 28, 2004

|

|

The Northern Wolffish (Anarhichas denticulatus) Slow-growing and sedentary, this fish can reach over 4 feet in length and 40 pounds in weight. Despite its bloated appearance, this is not a fatty fish, but a watery one. Northern wolffish is also known as the "jelly catfish" because of the unusually low protein and high water content of its muscle. Unpalatable to most people, the northern wolffish has had virtually no commercial value in Canada. It has stout "wolf-like" teeth which it uses to crush the shells of molluscs. Caught as "by-catch" in many commercial fisheries, the northern wolffish has experienced a 98% decline in numbers since the late 1970's, and it has been listed as a "threatened" species under Canada's Species at Risk Act (SARA). This provides a degree of legal protection. Unfortunately, the confinement of northern wolffish to Newfoundland waters places this species at a more imminent risk of extinction than the "endangered" Northern cod. To what lengths should or will Canada go to save this "fat cat?" |

|

|

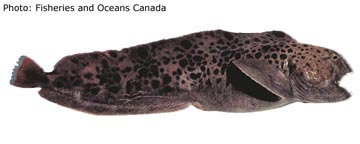

The Spotted Wolffish (Anarhichas minor) Related to the northern wolffish, but growing to a larger size and occupying a slightly wider geographical range, the spotted wolffish has firm, marketable flesh, and a tough skin suitable for tanning. It has therefore been of some commercial value. Also known as the leopardfish or spotted catfish, the abundance of this species has declined by 96% since the late 1970's. The spotted wolffish is also listed under SARA as "threatened."

|

The Honorable Geoff Regan, M.P.

Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, Canada

200 Kent Street

Ottawa, ON K1A 0E6

Min@dfo-mpo.gc.ca

Dear Mr. Regan,

How far do we bend wildlife protection laws in Canada for commercial interests?

The Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) has asked you to grant permission for commercial fishermen to continue to inflict “incidental harm” on two species of marine fish that have been listed as “threatened” in Canada. The northern wolffish and the spotted wolffish are caught as by-catch in various commercial fisheries in Atlantic Canada, and, barring your permission to continue catching them, harming either of these fish species or damaging their habitat is now legally prohibited in Canada under the Species at Risk Act (SARA).

Followed to the letter of the law, protecting these two fish species will unavoidably entail significant economic losses for the fishing industry. In June, 2004, as the legal requirement to protect these two threatened fish species came into full effect, a short paper was written by DFO advising you that continued harm inflicted by the fishing industry will “not threaten the survival and recovery” of northern and spotted wolffish. (DFO, 2004, “Allowable harm Assessment for Spotted and Northern Wolffish”)

Political concerns appear to have trumped conservation concerns in this case. DFO has chosen to minimize the extent to which populations of wolffish are depleted, and has tried to create an impression that, although wolffish are doing very poorly in Newfoundland waters, population components elsewhere in Atlantic Canada are stable and reasonably healthy. However, this is not true. Scientific evidence that directly contradicts this conclusion was omitted from DFO’s evaluation of wolfish and from the advice given to you.

DFO (2004) has written, regarding northern and spotted wolffish: “There is no evidence of a decline on the Scotian Shelf or in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the declines observed at the centre of their distribution have ceased…(and, criticizing the scientific analysis that led to SARA listing for wolffish)…The COSEWIC Reports did not examine trends in other areas, namely the Gulf of St. Lawrence or the Scotian Shelf/Bay of Fundy/Georges Bank, where the population indices have been stable.” (COSEWIC is the committee on the status of endangered wildlife in Canada.)

Both of these species, but especially the northern wolffish, are cold water fish that have essentially only ever been found in Newfoundland waters. This scientific observation was made of both northern and spotted wolffish: “in the western North Atlantic, it occurs in any numbers only off northeast Newfoundland. Elsewhere in Canadian waters, the species occurs only as an occasional stray.” (COSEWIC In Press (a) and (b))

Contrary to DFO’s recent advice, significant declines in the populations of spotted and northern wolffish, in the appearance of these “occasional strays,” have in fact been documented on the Scotian Shelf and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Thirty years of bottom trawl research surveys have been conducted by DFO on the Scotian Shelf. Well over 3000 trawl sets were done (1970 – 2000). A recent review of the accumulated data (Shackell and Frank, 2003, in press) indicated that the northern wolffish appeared in a total of only 12 of these trawl sets and the spotted wolffish in 14. Shackell and Frank noted specifically that, over the time series, the northern wolffish “demonstrated a significant decreasing trend in area occupied” on the Scotian Shelf. This is evidence of a decline in the presence of a rare fish, rather than “stable population indices.”

Both the northern and spotted wolffish have also experienced significant declines in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. “In the northern Gulf of St. Lawrence, where the (northern) wolffish is much less abundant (average no/tow over all years = 0.02), the overall population decline has also been very great, 97% from 1983 to 1994.” (O’Dea and Haedrich, in press (a)). An identical observation was made for the spotted wolffish, except that the average no/tow over all years was marginally greater at 0.03 (O’Dea and Haedrich, in press (b)). Both are rare fish, and disappearing.

|

|

|

Where are the wolffish? "Canadian distribution of the Northern Wolffish (shown in red)."

Map reproduced from SARA website on August

27, 2004. The distribution of this species is a key consideration for the

Minister of Fisheries and Oceans in his consideration of whether or not he

should issue a permit for continued "incidental harm" by fishermen. DFO

recently suggested that the northern wolffish has a more extensive

distribution than is supported by scientific data. Click on the following

link to check for current updates of this map.

(Note: The distribution map for spotted

wolffish on the SARA website looks identical to this one. Aug. 27/04) |

There is therefore no reason to offer reassurance to the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans that stable populations of wolffish might exist on the Scotian Shelf or in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Further, it is disingenuous of DFO to suggest that “population indices have been stable” for northern and spotted wolffish in the Bay of Fundy and on Georges Bank, because neither of these species extends its range into those areas (O’Dea and Haedrich, in press (a) and (b), COSEWIC in press (a) and (b), Leim and Scott, 1966). Indices “stable” at zero, perhaps? A different but related species of wolffish, the striped Atlantic wolffish (Anarhichas lupus), inhabits the more southern waters of the Bay of Fundy and Georges Bank. This species of wolffish is also in a “severely depleted” condition, in both Canadian and American waters, and the Atlantic wolffish has been designated as a species of “special concern” in Canada (DFO, 2000, Mayo, 2000). All species of wolffish in the northwest Atlantic have declined sharply in recent years, as have all large bottom-dwelling fish as a group, (this has been clearly documented on the Scotian Shelf (DFO, 2003, Choi et al, 2004)), leaving no reason to think that a few peripheral elements of the northern and spotted wolffish populations might be doing well anywhere in Canadian waters. However, this seems to be the idea that DFO is trying to float to the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans in its request for a permit for ongoing harm to the species by the fishing industry.

DFO has advised you this summer that “Between the late 1970’s and early 1990’s, the abundance of northern wolffish and spotted wolffish had declined by over 90% on the Grand Banks and Northeast Newfoundland/Labrador Shelf.” A decline of “over 90%” might suggest to you that perhaps nearly 10% of the original fish numbers remain. But the loss has been substantially greater than this, and relevant data extends past the early 1990’s. A scientific assessment in 2001, for instance, indicated for northern wolffish that “since 1978, abundance in the primary range off northeast Newfoundland is down by 98%. Numbers have declined steadily, the number of locations where the species occurs has declined, and the range may be shrinking.” (COSEWIC in press (a)). Similarly, the spotted wolfish is “down by 96%.” (COSEWIC in press (b))

By choosing to discuss only trends in “abundance,” DFO has failed to alert you to another serious indicator of decline in the wolffish populations: the average size of both northern and spotted wolffish has declined significantly over recent decades. The implied accelerated disappearance of large adult fish is widely recognized by scientists as a serious negative signal when it affects fish stocks, and this pattern has been generally associated with “over-exploitation.” But DFO has written, as “Rationale for Permitting”: “Given the steady state of the northern wolffish population trajectory and the increasing trajectory for spotted wolffish over the past 12 years, current levels of mortality do not appear to be negatively affecting the survival of the species.” This statement, however, is contradicted by the recent declining size of both wolfish species; whether they are succumbing as fishermen’s by-catch or to “natural” causes. Declining fish size is a cardinal signal of rising mortality, therefore the “current level of mortality” does indeed appear to be negatively affecting wolffish.

There seems to be substantial disagreement regarding the status of northern and spotted wolffish between DFO and the authors of the COSEWIC status report. This may help to explain the lack of distribution maps for these species on the SARA website. One of the COSEWIC report authors is Dr. Richard Haedrich, a well-respected, senior professor of Ocean Studies at Memorial University of Newfoundland. A consultation with Dr. Haedrich might provide you with a more complete view of the status of wolffish. Haedrich has argued that both northern and spotted wolffish qualify for the more urgent SARA designation of “endangered,” rather than “threatened” species, and he has advised “when in doubt, err on the side of the fish.”

Mr. Regan, DFO has asked your permission to allow continued harm to wolffish, not because the fish populations are stable, but because application of the SARA prohibitions will have a severe negative economic impact on the fishing industry.

“…northern and spotted wolffish…are captured in virtually every demersal fishery (about 35 directed species) in the Canadian Atlantic and Davis Strait. They are captured in various types of trawls, in gillnets, on longlines and in traps. There is little evidence of seasonality to the catches, thus, the only alternative would be fishery closures. Detailed economic analyses are not required to demonstrate that closures of Atlantic demersal fisheries would adversely affect the Atlantic economy and the livelihood of thousands.” (DFO, 2004)

Canada may choose to place a higher value on the “livelihood of thousands” than on the survival of each and every indigenous species, and relatively obscure animals like the wolffish might therefore be knowingly sacrificed for this reason. Is this happening now? This strategy contravenes current federal law, but if this is what DFO and the fishing industry feel they must do, then why not openly admit it? Perhaps this course of action is reasonable, perhaps it is not, but to pretend to be doing something else is wrong. It seems now that taxpayers are funding federal scientists to find ways to avoid complying with the law. Perhaps Canadians should be asked if they would prefer to have the SARA law changed?

The “livelihood of thousands” in the Atlantic fisheries now depends largely on harvesting crustaceans; shrimp, crab and lobster. And the persistent quibbling over one fish at a time serves effectively to avoid focusing our thoughts on the profound level of change that we have inflicted on the ocean ecosystem itself by centuries of fishing (Choi et al, 2004, DFO, 2003). At this point, a more realistic assessment of the future prospects of wolffish, all other large finfish, fishermen and crustaceans, might be that the cumulative effects of fishing have subtly eroded the strength of the living ocean web to the point where it has now fallen below the level where large finfish can be widely supported. To continue working, fishermen in Atlantic Canada now need to take predominantly crustaceans. Populations of crustaceans will be supported for some time yet, but their substantial harvest entails lowering ocean system vitality further. Therefore, the period of profitable crustacean harvesting will ultimately be limited, as was that for fish (however, the time will be much shorter for crustaceans). Remnant fish populations will continue to decline and disappear during the years of heavy crustacean harvesting, so the preservation and “recovery” of individual finfish species during this time is unrealistic.

Signs of stress and decline are now seen in the crustaceans that currently support the Atlantic Canadian fishing industry, in shrimp, crab and lobster. This you already know. Fisheries are in a “post-groundfish” phase now, and will shift at some future time to a “post-crustacean” phase. Unfortunately, however, this will not mean a resurgence of the groundfish, as some people believe it will, because the changes to the ocean system have included a lowering of overall food production below the point where such fish can thrive. Unthinkable? Maybe, but as I have told you before, broad, unmistakable signals of this fundamental productivity decline are evident throughout the ocean today. And fishing can reasonably be implicated as a cause. The failure of fisheries science to predict this ominous complication has not prevented its occurrence, but it seems to have stymied efforts to understand what is happening.

Rather than a “cod recovery plan” or a “wolffish recovery plan,” or any other single-species conservation initiative, we urgently need a more determined and comprehensive “ocean ecosystem recovery plan.” This will be more difficult in some ways, but simpler in others. Scientists today need to visualize our approach to ocean life as a salvage operation, as providing “intensive care” for a living entity that has been seriously damaged, rather than blindly persisting in seeking new ways to drain ever more protein from a disabled food web. This concept is naturally anathema to fishing interests, so DFO will be unable to grapple with it. But this is where SARA might help…if DFO is not permitted to sidestep the law. Regardless, nature will continue to function according to her own rules, and she will not be forced into the “sustainable fishing” box that we have created for our psychological comfort. We can choose to remove the blinders, or we can leave them on, but people will soon be forced to see the bitter truth that we simply cannot have our fish and eat them too – not indefinitely. Commercial fishing has now pushed the bigger fish into the endgame, and it is impossible to “facilitate” the recovery of species like wolffish and cod while continuing to prosecute other fisheries.

Mr. Regan, I suggest that the time for Canadians to bite the bullet is now, before a multitude of larger marine animal species are lost irretrievably from our waters. This might realistically happen in the near future, and with surprising speed, but there is still a chance that we might be able to take preventative action. Something needs to jam the gears of destruction, and it might as well be the otherwise “useless” wolffish. Refuse DFO’s request for the “permit” because they provided you with misleading advice, and because the wolffish do, in fact, qualify for legal protection in Canada at this time. (These fish need a good lawyer…)

Challenge DFO to begin to take an honest “precautionary, ecosystem approach” when setting measures to conserve marine life, and more importantly, challenge them to admit how many puzzle pieces they have today that they cannot fit into the mould they started out with, into the “sustainable fishing” box. Challenge – or perhaps “allow” - DFO scientists to act with a level of “precaution” that reflects the many fundamental aspects of the marine ecosystem that they do not understand. Many of DFO’s decisions, such the recent call for the wolffish permit, are heavily distorted by a short-term, pro-industry bias, and this must make a difficult work environment for true scientists.

Organizing an inquiry into the irregularities plaguing DFO Science would be appropriate, as would your reinstating something along the lines of the former Minister’s Advisory Council on Oceans.

Sincerely,

References

Choi, J. S., K. T. Frank, W. C. Leggett, and K. Drinkwater, 2004. Transition to an alternate state in a continental shelf ecosystem. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 61: 505-510.

COSEWIC In Press (a). COSEWIC assessment and status report on the northern wolffish Anarhichas denticulatus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 21 pp.

COSEWIC In Press (b). COSEWIC assessment and status report on the spotted wolffish Anarhichas minor in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 22 pp.

DFO, 2000. Wolffish on the Scotian Shelf and Georges Bank and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence (Subarea 4 and Div. 5Yze). DFO Sci. Stock Status Report A3-31(2000).

DFO, 2002. Wolffish in Division 2GHJ,3KLNO, and Subdivisions 3Ps/Pn. DFO Science Stock Status Report A2-16(2002).

DFO, 2003. State of the Eastern Scotian Shelf Ecosystem. DFO Ecosystem Status Report 2003/004.

DFO, 2004. Allowable Harm Assessment for Spotted and Northern Wolffish. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Stock Status Report 2004/031.

Leim, A. H. and W. B. Scott, 1966. Fishes of the Atlantic Coast of Canada. Fisheries Research Board of Canada, Bulletin No. 155. Ottawa, 1966.

Mayo, Ralph, 2000. Atlantic Wolffish. Status of Fisheries Resources off Northeastern United States – Atlantic Wolffish. (online at: http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/sos/spsyn/og/wolf/ )

O’Dea, N. R., and R. L. Haedrich. In Press (a). COSEWIC status report on the northern wolffish Anarhichas denticulatus in Canada, in COSEWIC assessment and status report on the northern wolffish Anarhichas denticulatus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-21 pp.

O’Dea, N. R., and R. L. Haedrich. In Press (b). COSEWIC status report on the spotted wolffish Anarhichas minor in Canada, in COSEWIC assessment and status report on the spotted wolffish Anarhichas minor in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-22 pp.

Shackell, N. L. and K. T. Frank, 2003. Marine fish diversity on the Scotian Shelf, Canada. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems (in press). ( www.marinebiodiversity.ca/fr/pdfs/diversity_AQC_shackell1.pdf )

Sign My Guestbook

![]() View My Guestbook

View My Guestbook