Seal diseases in Canada – update October 23, 2006

(in follow up to earlier articles 'seal

products may endanger human health' and 'letter to

Chuck Strahl')

by Debbie

MacKenzie

Codmother@bellaliant.net

“Sometimes I think that with friends like the

government, we don’t need enemies.”

– Tina Fagan, Canadian Sealers

Association

Human consumers of seal products may be exposed to dangerous infectious diseases because Canada processes seals as fish instead of meat. This allows seal processors to avoid using infection control measures that are mandatory for processors of all other commercial meat products, measures that are designed to protect human consumers from contracting mammal diseases from meat, such as tuberculosis, brucellosis, rabies, trichinosis and others.

|

Clip from the cover of a recent Canadian government publication...detailing many contagious ailments of marine mammals that are never found in fish. Several of these can also threaten human health. Yet, Canada processes seals for commercial marketing without screening for these diseases, because the Canadian Food Inspection Agency has determined that "seals are classified as fish."

|

Seals are processed in accordance with fish inspection protocols that were written for cold-blooded aquatic animals. This is simpler and cheaper than implementing meat inspection protocols. Using fish inspection for seals also serves to avoid the problem of seal carcasses being condemned and deemed inedible by veterinary inspectors. Therefore, using fish inspection for seals supports Canada’s ‘fullest possible commercial use of seals’ policy, although the practice is scientifically unsound from a public health perspective.

In April 2006, I tried to bring this problem to the attention of Canadian government departments responsible for the seal hunt and for consumer product safety, posting an article on this website and writing letters. I thought that the mandate of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) should lead this department to issue a directive to seal processors ordering them to change from using the fish inspection protocol to using the meat inspection protocol, based on scientific evidence that seals pose meat threats to consumers. After all, the CFIA oversees the application of veterinary knowledge to protecting public health. Here is an update on the issue.

1. Replies received from government (DFO, CFIA and Health Canada)

2. The legal loophole that allows seals to be processed as fish (The CFIA interprets the Fish Inspection Act as being applicable to seals as well as fish, while an exemption for marine mammals under the Meat Inspection Regulations is used to bypass enforcement of normal meat hygiene directives in seal processing.)

3. Canadian laws that provide no exemptions for seals – are legal obligations being avoided in these areas? (the Food and Drugs Act and the Health of Animals Act)

4. Focus on brucellosis in seals: how much do we know, and how has Canada handled this information? (Major question: why has the Canadian government provided public education and food safety programs for hunters and consumers of marine mammals in the Arctic region only, when evidence of seal disease was found in the Arctic and Atlantic Regions simultaneously and the bulk of seals killed for human consumption are hunted and processed in the Atlantic Region?)

5. Wildlife Disease Surveillance in Canada

6. What does the fishing industry think? (Marketing seal products for human consumption has been difficult, and the industry seems not to understand why I have tried to raise a food safety concern about their seal products.)

7. Conclusion

1. Replies received from government (DFO, CFIA and Health Canada)

Responses from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) (Summary: food safety is not DFO’s business or responsibility, despite their ‘fullest possible commercial use of seals’ policy, that has driven recent efforts of seafood processors to market seal oil and seal meat for human consumption.)

A response to my original letter of concern was received from Loyola Hearn, federal Minister of Fisheries and Oceans:

June 23, 2006

Dear Ms. MacKenzie:

Thank you for your correspondence of 25 May, 2006 concerning “Seal product Health Hazard”.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) is responsible for the management, conservation and protection of Canada’s marine resources, including marine mammals. DFO’s research in marine mammals diseases is conducted in the interest of conservation of the resource, particularly for species at risk or for species of commercial or subsistence interest.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) is Canada’s federal food safety, animal health and plant protection enforcement agency. Health Canada establishes food safety guidelines which CFIA enforces. In your e-mail you forwarded a message which you had originally sent to the Honourable Chuck Strahl, Minister of Agriculture who is responsible for the CFIA. You also copied the Honourable Tony Clement Minister of Health.

Since your concerns focus on the processing and consumption of seal meat and the potential of transmission of zoonotic diseases I am referring your letter back to the Ministers of Agriculture and Health

Sincerely

Loyola Hearn, P.C., M.P.

cc: The Honourable Chuck Strahl, P.C.

The

Honourable Tony Clement, P.C., M.P.

A different letter was sent to Faith Scattolon, and a response received. Here is that correspondence:

June 2, 2006

To: Faith Scattalon

Acting

Regional Director General, DFO Maritimes

From: Debbie MacKenzie

Grey Seal

Conservation Society (GSCS)

Re: Health and Disease-status of Seals

Dear Ms. Scattolon,

I am writing as the chair of the Nova Scotia-based Grey Seal Conservation Society (GSCS) to ask that the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) collaborate with us in undertaking a health assessment of seals in the Maritimes Region.

Very little has been published in the scientific literature regarding the health status of seals living in this area (grey seals, harbour seals, harp seals and hooded seals). And evidently, marine mammal research at DFO currently does not include any systematic monitoring of seal health.

However, the assessment of the health- or disease-status of seals is part of the responsibility of DFO, and this matter carries considerable public significance.

Given that seal health was not included in the new National Aquatic Animal Health Program, the Grey Seal Conservation Society is hereby requesting that a DFO-facilitated seal health assessment and monitoring project now be initiated in the Maritimes Region.

Please arrange for DFO to meet with GSCS at the earliest possible date to discuss this matter. Thank you.

Sincerely,

Debbie MacKenzie

Reply:

July 10, 2006

Dear Ms. MacKenzie:

Thank you for your letter of June 2, 2006 in which you enquired about disease monitoring of marine mammals by Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO).

The department has two marine mammal disease specialists, Dr. Lena Measures at Institute Maurice Lamontagne and Dr. Ole Nielsen in the Central and Arctic Region. In Newfoundland and Labrador Region, Dr. Garry Stenson at DFO’s Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Centre works with provincial veterinarians to deal with specific marine mammals issues. Here in the Maritimes Region, DFO collaborates with the Atlantic Veterinary College, primarily through Dr. P-Yves Daoust. Overall, these researchers maintain close contact with marine mammal biologists working in other DFO regions across the country and with disease specialists elsewhere in Canada and the United States.

This network of scientists deals with marine mammal strandings and disease issues. Although it is impossible to predict disease outbreaks, there are several mechanisms, including a National Wildlife Disease Strategy, which provide a framework for monitoring unusual marine mammal mortality events that might be linked with disease. The national strategy involves three components:

1) coordination with individuals in the field within and outside of government

to report unusual mortality events

2) ongoing sample collection and testing for new diseases; and

3) dedicated research of particular marine mammal diseases.

The department is aware of the potential for diseases to negatively affect marine mammal populations, however, it is believed that current research and monitoring by DFO and others is sufficient to identify significant disease outbreaks. Given that disease outbreaks are infrequent in marine mammals and the difficulty of predicting outbreaks, it would not seem prudent to invest more resources at this time. Issues affecting marine mammal meat for either consumption or human health are the mandate and responsibility of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and Health Canada.

Yours sincerely,

Faith G. Scattolon

A/Regional Director-General

Maritimes Region

Responses from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) (Summary: the CFIA is responsible for implementing the Fish Inspection Act, the Meat Inspection Act and the Health of Animals Act, and this agency therefore seems to have the greatest responsibility for the safety of seals for human consumption. CFIA’s response was to tell me that what I had complained about was true: that seal products for human consumption are currently inspected under the Fish Inspection Act. However, CFIA did not seem to perceive this as a problem, nor did they acknowledge or respond to the fact that Fish Inspection protocols do not include screening or “critical control points” for zoonotic pathogens that are known to affect seals. (Zoonotic pathogens are infectious diseases in animals that can also cause illness in humans.) CFIA also told me that Health Canada would be responding to my concern.)

Reply to my letter to Chuck Strahl:

July 18, 2006 Quote: 450569

Dear Ms. MacKenzie:

On behalf of the Honourable Chuck Strahl, I wish to thank you for your letter regarding zoonotic pathogens in Canadian seal products. The Minister appreciates being made aware of your views and has asked me to convey to you the following information.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) does not endeavour to conceal the existence of reportable diseases in animals. The presence of brucellosis in several wild animal populations of Canada is well documented. The types of brucellosis that occur in Canada’s marine mammal population differ from that found in bison in Wood Buffalo National Park and from the strains of the brucellosis that are found in the wild ungulates of Canada’s Arctic.

In general, efforts to increase public awareness concerning any potential zoonotic threat that may be posed by sylvatic brucellosis falls outside the mandate of the CFIA. The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), in collaboration with its provincial and territorial counterparts, has the lead role in this area. You may wish to approach those provincial and territorial agencies with your concerns. It is noted that you copied your correspondence to the Minister of Health, the Honourable Tony Clement, who is responsible for the PHAC.

Canada has developed, and is recognized for, one of the safest food systems in the world based on continuous improvement, respect for science based international strategies and audits conducted by foreign governments. Food safety and consumer protection are the CFIA’s top priorities. The CFIA’s role is to enforce the food safety and quality standards established by Health Canada.

The CFIA enforces the Fish Inspection Act and Regulations as well as the Food and Drugs Act and Regulations. Seals are classified as fish under the Fish Inspection Act and Regulations, and are therefore subject to the same requirements applicable to fish destined for human consumption, whether domestically on import or, for export.

Establishments processing seal products for export (whether interprovincially or internationally) must be registered by the CFIA and must be constructed and operated to meet the sanitary requirements set out in the Fish Inspection Regulations.

In order to be registered by the CFIA, the establishments must develop, implement and maintain a Quality Management Program (QMP) plan that describes the controls that will be followed to process the seal products to satisfy the Canadian requirements for safety, wholesomeness and identity. This QMP plan includes HACCP (Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point) controls for food safety based on internationally recognized standards, and includes considerations for contaminants of public health relevance such as PCBs and dioxins.

In addition, the CFIA is responsible for enforcement of those sections of the Food and Drugs Act and the Consumer Packaging and Labelling Act as they apply to food (fish). The CFIA is responsible for verifying that the fish processing industry operates within the legislative requirements to ensure that fish and fish products are safe, wholesome and labelled appropriately.

Further details regarding the CFIA’s fish inspection activities can be found on the CFIA website at www.inspection.gc.ca/english/anima/fishpoi/fispoie.shtml .

I trust you will find this information useful. Again, thank you for writing.

Sincerely,

Christine Bakke

Policy Advisor

cc: Mr. William King

Responses from Health Canada (HC) (Summary: Health Canada tested the sample of seal oil capsules that I left with them for Brucella and reported back to me that the result of the test was negative. (However, international standards (FAO/WHO) do not describe random sample testing as an adequate control strategy for the potential consumer hazard of contracting brucellosis from infected food animals.) An anonymous employee at Health Canada’s Natural Products Directorate also sent a reply to me outlining the licensing requirements for Natural Health Products (However, the seal oil capsules that I’d brought to their attention are not currently licensed as a NHP.) Health Canada also responded by telling me that no human cases of brucellosis have been documented in Canada as originating from contact with seals, and by describing their advice regarding consumer safe food handling practices for meat. This response from HC side-stepped the food safety protocols about which I’d tried to initiate discussion: the pre-market activities in which the government and the industry ensure that zoonotic pathogens are not present in consumer meat products.)

Subj: In response to your correspondence addressed to

the Minister of Health – 06 – 005404 (EH)

Date: 9/20/2006 3:16:04 PM Atlantic Standard Time

From:

cst@hc-sc.gc.ca

To:

Codmother2@aol.com

Dear Ms. MacKenzie:

Thank you for your correspondence of May 25, 2006, addressed to the Honourable Tony Clement, Minister of Health, concerning the safety of Canadian seal meat. I regret the delay in responding.

The consumption of raw meat, butchering practices, and post-mortem examinations have provided cases of human exposure to Brucella spp. from marine mammals. Despite this, there are no reported cases of human infection with marine Brucella spp. In addition, Health Canada recommends that raw meats be handled and cooked properly.

The recommendations provided by the Canadian Partnership for Food Safety Education, a coalition of industry, consumer, government, health and environmental organizations, should be followed in order to improve consumer understanding of foodborne illness and measures that can be taken to decrease the risk of illness. Simple measures such as cleaning, cooking, chilling and separating, will minimize the potential for foodborne illnesses from handling raw meat. In conclusion, at the present time, there is minimal risk to the health of marine mammal hunters or consumers of seal products.

I hope the foregoing will prove useful to you. Thank you for writing.

Sincerely,

William King

Chief of Staff

Regarding the safety of seal oil, I received a response from Health Canada’s Natural Health Product Directorate:

From:

nhpd-dpsn@hc.sc.gc.ca

To:

Codmother2@aol.com

Subj: From Health Canada re: Seal Oil Contamination and Terra Nova Omega 3

Seal Oil Capsules

Date: Mon, 25 Sep 2006 12:21 PM

Ref: 06-121585-789

Dear Ms. MacKenzie:

This is in response to your e-mail of June 16, 2006, addressed to Health Canada’s Atlantic Operational Centre regarding seal oil contamination and the product Terra Nova Omega 3 Seal Oil Capsules. We apologize for the lengthy delay in responding to you.

Your e-mail was forwarded to the Natural Health Products Directorate (NHPD) as we are the federal entity responsible for the regulation of natural health products in Canada, including seal oil health products.

All natural health products must undergo a pre-market review before they can be sold in Canada. During this review, Health Canada assesses the evidence supporting the safety, efficacy and quality of the product and ensures adherence to appropriate labeling requirements. In addition, the NHPD also ensures that the manufacture of natural health products follows good manufacturing practices. Only natural health products which meet these requirements will be authorized for sale in Canada.

Brucellosis contamination is highly unlikely in natural health products that contain seal oil as the process used for the rendering of seal fat to produce the oil would kill any presence of the bacteria. As indicated above, all natural health products are thoroughly reviewed and only those that are found to be safe, effective and of high quality are authorized for sale. Manufacturers must demonstrate that their manufacturing process involves rendering and that there is a quality control system in place to minimize any risk of product contamination in order to receive market authorization from the NHPD.

With respect to Terra Nova Omega 3 seal oil capsules, a sample of this product was tested by a Health Canada laboratory and found not to contain Brucella.

Thank you for writing. We hope this information is of use to you. Again, we apologize for the delay in our response.

The Natural Health Products Directorate

Health Canada

**********Original Complaint to HPFBI AOC***********

Dear Ms. Kasina,

My concern about the seal oil is firstly that it has not been produced in compliance with section B.09.002 of the Food and Drugs Act, which reads:

“Animal fats and oils shall be fats and oils obtained entirely from animals healthy at the time of slaughter…”

It is my understanding that no health inspection is conducted on the seals from which the seal oil is obtained. In Canada, only “official veterinarians” are qualified to attest to the health of animals for human consumption, but this has not been made part of the processing of seal oil. This leaves consumers exposed to potential zoonotic disease risks.

That is why I originally asked CFIA to review the HACCP and QMP’s used by the seal processors.

In addition, I am also concerned to note that materials used to advertise the seal oil describe a processing method that does not include heat treatment or other commercial sterilization. In addition to zoonotic diseases, I am concerned that this potentially poses a risk of botulism poisoning of consumers.

The seal oil capsules that I have are “Terra Nova Omega-3” purchased at Planet Organic on Quinpool Road, Halifax. I will bring the label to your office for your inspection, but as I have explained, my concerns extend beyond labeling. Here is an internet advertisement for the product I bought http://www.tidespoint.ca/health/sealoil.shtml : “Omega 3 Plus+ Premium Natural Harp Seal Oil and Omega 3 Natural Premium Harp Seal Oil are manufactured by a process of cold processing, centrifuging and mechanical filtering. No chemical solvent is involved. The entire manufacturing process is under strit (sic) sanitary conditions, in accordance with Canadian Food & Drug Regulations and Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) standards.”

As we discussed, I am also concerned that the Department of Fisheries and Oceans has included inappropriate health claims for seal oil on its website. “Seal oil, once extracted, is marketed in capsule form, which is rich in Omega-3 acids. The fatty acids are known to be helpful in preventing and treating hypertension, diabetes, arthritis and many other health problems.”

Beyond Terra Nova Omega-3 seal oil, I am concerned by advertising tactics used by the larger industry association that produces and promotes seal oil. Look at the explanation of the purpose of the CAO3M:

http://www.omega3canada.ca/purpose.html

Their third point explains to foreign buyers: “To be able to sell marine-based Omega 3 products in Canada, all companies must get both Product and Site Licenses from the Natural Health Products Directorate of Health Canada. On the Natural Health Products web site one can find the following description: ‘Through the Natural Health Products Directorate, Health Canada ensures that all Canadians have ready access to natural health products that are safe, effective and of high quality, while respecting freedom of choice and philosophical and cultural diversity.’” (…I think this might mislead buyers into thinking that these manufacturers actually already have NHP product licenses for their seal oil.)

Their sixth point goes on to explain: “Canadian manufacturers of long chain Omega 3 products from marine sources want to ensure that people worldwide have the same access as Canadians to natural health products that are safe, effective and of high quality. Since the Natural Product Regulations do not permit the use of the NHP license number on products marketed outside of Canada, Canadian manufacturers of marine-based long chain Omega 3 products needed a mechanism to advertise the quality of its products. To this end, they decided to form an Association and to create a distinctive logo” (…I think this might mislead foreign buyers into thinking the reason no NHP numbers appear on the product they receive is that some Canadian rule prohibits this. Note how they wrote “Natural Products Regulations” instead of “Natural Health Products Regulations.” Foreign buyers might mistakenly believe that the same type of seal oil capsules being sold to them are for sale in Canada with NHP numbers on the labels.)

Here is a promotional site from a member of the industry association that posted the above information, claiming “approval for sale in Canada by Health Canada” for their seal oil capsules: http://www.omegavite.com/index2.html - This is misleading, because it refers to an approval given earlier for them to claim seal oil is a FOOD source of omega-3, like the omega-3 eggs, but a form of approval no longer given or required by Health Canada in my understanding. Correct me if I am wrong. Buyers, including Canadians who view this website, might misinterpret the claim to mean that Omegavite seal oil has Health Canada approval as a NHP.

Please investigate these matters, and respond to me in writing. As you may be aware, I have posted a report of my own investigation into the safety of seal products on the internet: http://www.fisherycrisis.com/seals/seal%20products.htm

CFIA’s response was to tell me that the entire matter of my complaint, including the safety of seal meat and pelts for human consumption had been passed on to Health Canada. Can you let me know who will be the person investigating these aspects of my complaint?

thank you,

Debbie MacKenzie

--

Since the anonymous writer from NHPD did not answer my questions, I wrote back at once:

Subject: Re: From

Health Canada re: Seal Oil Contamination and Terra Nova Omega 3 Seal Oil

Date: 9/25/2006 11:30:44 A.M. Pacific Standard Time

From:

Codmother2@aol.com

To:

nhpd_dpsn@hc-sc.gc.ca

Dear NHPD,

Thank you for the reply. Please answer a few simple yes/no questions for me:

1. Has the product Terra Nova

Omega 3 Seal Oil Capsules met your criteria for approval as a Natural Health

Product?

2. Does this product have a NHP number?

3. Does the word "rendering," as you used it in your reply, mean that the seal

oil must be heat treated?

4. Is the Terra Nova Omega 3 Seal Oil heat treated?

5. Is "healthy at the time of slaughter" (the standard in the Food and Drugs Act

relating to animal oils) part of the "quality control system" that the NHPD

expects to be in place when products are derived from animals?

6. Do you consider seals to be animals?

7. Do the makers of Terra Nova Omega 3 Seal Oil Capsules conduct health

inspections on seals at the time of slaughter that comply with normal meat

inspection standards in order to guarantee that consumers will not be exposed to

bacterial zoonoses?

8. Is random product testing considered to be an adequate or critical point to

control the hazard of brucellosis transmission through food products?

thank you

Debbie MacKenzie

(No reply has been received to this letter yet, but I will add it to this webpage when it arrives.)

2. The legal loophole that allows seals to be processed as fish (The CFIA interprets the Fish Inspection Act as being applicable to seals as well as fish, while an exemption for marine mammals under the Meat Inspection Regulations allows the CFIA to bypass enforcement of normal meat hygiene directives in seal processing.)

Under Canada’s Fish Inspection Act:

‘“fish” means any fish, including shellfish and crustaceans, and marine animals, and any parts, products or by-products thereof.’

The CFIA evidently interprets ‘animal’ here broadly enough to include mammals such as seals, because the words ‘seal’ and ‘mammal’ themselves appear nowhere in either the Fish Inspection Act or Regulations, despite Christine Bakke (CFIA) having written to me that “Seals are classified as fish under the Fish Inspection Act and Regulations…” Seals must be “classified as fish” by inference under this law, because they are not so classified openly. Can ‘animal’ under this law perhaps be taken to mean any organism in the Kingdom Animalia?

Under the Fish Inspection Regulations ‘marine animals’ are required to be checked only for problems known to affect cold-blooded fish. However, it seems there does exist enough legal scope for the CFIA to decide to impose meat inspection rules on seals, nevertheless. That is because the Fish Inspection Act prohibits anyone from selling “unwholesome” fish, and under the Fish Inspection Regulations:

‘“unwholesome”, with respect to fish, means fish that has in or upon it bacteria of public health significance or substances toxic or aesthetically offensive to man.’

So, if the CFIA became aware that commercially harvested seals carried brucellosis, or other bacteria of public health significance, then the sale of seal products should reasonably be halted by the CFIA until this particular health hazard has been adequately controlled by the processors, which would necessarily entail a meat inspection protocol…whether or not seals are still viewed as ‘fish’.

The Fish Inspection Regulations lay out sanitary requirements for fish processing establishments, including the following prohibition in schedule 2:

“5. Animals are not permitted inside an establishment.”

Interpreting this might be troublesome…because if ‘animals’ legally includes fish, then fish are barred from fish processing establishments. On the other hand, if ‘animals’ in this case refers to non-human mammals, then dogs, cats, rats, bats and seals are prohibited. That interpretation of ‘animals’ would make a certain sense, because bacterial hazards can be introduced by non-human mammals. Another possible interpretation is that ‘animals’ encompasses the entire Kingdom Animalia…and while that would sensibly bar seagulls from entering fish processing establishments, humans would be barred too, which would seem, on the face of it, to be a ludicrous interpretation. That would be about as off-base as interpreting the Fish Inspection Act to mean that seagulls, puffins, loons and seals can be legally processed as fish, or that fish processing can be applied equally to absolutely any other ‘marine animals’…which it could then be argued carries the same meaning as ‘seagoing animals’…which could then be interpreted as meaning even the fishermen themselves. Even the wharf rats, I suppose. At what point did this line of reasoning cross the line to ridiculous and dishonest?

It would have been helpful had the writers of the Fish Inspection Act and Regulations included clear definitions ‘marine animals’ and ‘animals.’ My full reading of the Fish Inspection Regulations leads me to conclude that the term ‘marine animals’ was added to the definition of ‘fish’ after ‘shellfish and crustaceans’ to include marine invertebrates that do not have shells, i.e. squid and octopus. ‘Marine animals’ was never meant to permit mammals or birds to be processed under the Fish Inspection Act. This conclusion is supported by the definition of ‘animals' in the related Meat Inspection Act, a law approved the same year (1985) and also enforced by the CFIA.

Under Canada’s Meat Inspection Act :

‘“animal” means any animal in the class of mammals or birds… “carcass” means the body of a dead animal…and “meat product” means (a) a carcass, (b) the blood of an animal or a product or by-product of a carcass…”’

Therefore, seal products are legally meat in Canada, whether or not they are also legally fish, because they are mammals. Seals are definitely classified as meat, and no creative interpretation of the legal wording is needed to draw that conclusion. Under the Meat Inspection Regulations, however, an exemption from the application of the Act is applied to marine mammals in section 3:

“MEAT PRODUCTS EXEMPTED FROM THE APPLICATION OF THE ACT

3. (1) Sections 7 to 9 of the Act do not apply in respect of

(a) a shipment of meat products weighing 20 kg

or less that is intended to be used for non-commercial purposes;

(b) a shipment of meat products that is part of an immigrant's or

emigrant's effects;

(c) a meat product derived from a

marine mammal;

(d) a prepared pet food;

(d.1) feed, as defined in subsection 2(1) of the Feeds Regulations,

1983;

(e) a meat product carried on any vessel, train, motor vehicle, aircraft

or other means of transportation for use as food for the crew or passengers

thereof;

(f) a carcass of a game animal, or a part of a carcass of a game animal,

including the carcass or part of the carcass of the animal that is considered to

be a game animal in another country, that is to be used for non-commercial

purposes;

(g) gelatin, bone meal, collagen casing, hydrolyzed animal protein,

monoglyceride, diglyceride, fatty acid and the products resulting from the

rendering of inedible meat products;

(h) a meat product, the total amount of which does not weigh more than

100 kg, destined and used for analysis, evaluation, testing, research or an

international food exhibition;”

The list of exemptions goes on, but the intent of allowing these exemptions seems clear: meat products not destined for commercial sale for human consumption are exempt from the strict meat inspection rules that are applied whenever meat products are produced for commercial sale for human consumption. These Regulations were approved in 1990, before the government's 'fullest possible commercial use of seals' policy came into effect, so the commercial sale for human consumption of seal meat and seal oil may not have been anticipated by the legislators. The exemption may have been originally intended to ease the health screening requirements for those processing and marketing seal pelts, because they are "meat products"(?) It is interesting to note that further down in the exemption list is a reference to some types of wild game:

“(3) Section 8 of the

Act does not apply in respect of the following meat products:

(a) a meat product

transported by a person for non-commercial purposes;

(b) a meat product that is identified for use as

animal food or for medicinal purposes and used for animal food or for medicinal

purposes;

(c) [Repealed, SOR/94-683, s. 4]

(d) a meat product that is produced in a federal

penitentiary and sent or conveyed to another federal penitentiary;

(e) a meat

product derived from a muskox, caribou or reindeer that has not been kept in

captivity, if the meat product is edible; and”

The Section 8 exemption for muskox, caribou and reindeer allows inter-provincial trade of these meats (“if edible”) but they remain barred from import and export marketing (probably because food safety is somewhat lower since no ante-mortem control or veterinary inspection of hunted wild animals is possible). The CFIA provides a mobile meat inspection service for northern Canadians who are involved in hunting and processing these wild meats for commercial marketing. CFIA inspectors rule on which carcasses are “edible” and which ones are “condemned”. Muskox, caribou and reindeer are not treated as 'fish.' Herds of wild caribou and reindeer living in northern Canada are known to be affected by brucellosis and other zoonotic diseases, and presumably the CFIA meat inspectors take appropriate measures to exclude infected animals from those that are sent to market as meat for human consumption. Clearly, the standard should be no less for any commercial trade in seal meat.

The intent of Canada’s meat and fish inspection laws seems clear to the lay interpreter, and one goal was to avoid having meat processed as fish. For example, general provisions of the Fish Inspection Regulations include, in part:

“3. (2)…these Regulations do not apply to…(b) a food that meets the following specifications, namely…(ii) the food is commonly recognized as a meat product, having regard to…(B) the common name of the food…(D) the historical recognition of the food as a meat product…”

Any Newfoundlander can tell you that seal is not a fish, that seal is meat.

Since 1990, potentially serious zoonotic disease has been found in seals at the same time as the fishing industry has turned towards marketing them for human consumption. To be safe, sane and ethical, Canada’s Parliament should now repeal the marine mammal exemption under section 3 (1) ( c) of the Meat Inspection Regulations. Even before this is done, however, the CFIA has the power to impose appropriate food safety measures on seal processing.

3. Relevant Canadian laws that do not exempt seals: have legal obligations being avoided in these areas? (the Food and Drugs Act and the Health of Animals Act)

Health Canada is responsible for the Food and Drugs Act and Regulations, yet they have refused to address my concern that under this law seal oil can only be obtained from ‘healthy animals’. No exemptions, for seals or any other animals, are listed from the requirement that section B.009.02 of the Food and Drugs Regulations be applied in the production of Animal Fats and Oils: ‘Animal fats and oils shall be fats and oils obtained entirely from animals healthy at the time of slaughter.’

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) is responsible for implementing the Health of Animals Act, which provides no exemption for seals or other types of animals, and which requires in section 5 (2) that:

“Immediately after a person who is a veterinarian or who analyses animal specimens suspects that an animal is affected or contaminated by a reportable disease or toxic substance, the person shall so notify a veterinary inspector.” (and ‘veterinary inspector’ is defined as ‘a veterinarian designated as an inspector…’) So, under this Canadian law, any veterinarian, or any ‘person who analyses animal specimens’ has a legal obligation to report their ‘suspicion,’ should they form one, that an ‘animal’ is affected by a reportable disease…and the list of reportable diseases includes ‘brucellosis.’

The Health of Animals Act goes on to say what can happen after a veterinarian or other person notifies a veterinary inspector of their suspicion that an animal is affected by a reportable disease:

“22 (1) Where an inspector or officer suspects or determines that a disease or toxic substance exists in a place and is of the opinion that it could spread or that animals or things entering the place could become affected or contaminated by it, the inspector or officer may in writing declare that the place is infected and identify the disease or toxic substance that is believed to exist there….22 (2) When the declaration is delivered to the occupier or owner of the place to which it relates, the place, together with all contiguous lands, buildings and other places occupied or owned by the occupier or owner, constitutes an infected place…23 (1) For the purpose of preventing the spread of a disease or toxic substance, an inspector or officer may in writing declare that any land, building or other place, any part of which lies within five kilometres of the limits of a place declared to be infected under section 22, is infected and identify the disease or toxic substance that could spread there…25 (1) Subject to any regulations made under paragraph 64 (1) (k), no person shall, without a license issued by an inspector or officer, remove from or take into an infected place any animal or thing…26 A place, or any part of a place, that has been constituted to be an infected place…ceases to be an infected place when an inspector or officer declares in writing that the disease or toxic substance described in the declaration (a) does not exist in, or will not spread from, the place or the part of the place; or (b) is not injurious to the health of persons or animals….27 (1) Where the Minister believes that a disease or toxic substance exists in an area, the Minister may declare the area to be a control area, describe the area and identify the disease…(2) The Minister may take all reasonable measures consistent with public safety to remedy any dangerous condition or mitigate any danger to life, health, property or the environment that results, or may reasonably be expected to result, from the existence of a disease or toxic substance in a control area. (3) The Minister may make regulations for the purposes of controlling or eliminating diseases or toxic substances in a control area and of preventing their spread, including regulations (a) prohibiting or regulating the movement of persons, animals or things, including conveyances, within, into or out of a control area; (b) providing for the establishment of zones within a control area and varying measures of control for each zone; and (c) authorizing the disposal or treatment of animals or other things that are or have been in a control area. (4) Where an inspector or officer believes on reasonable grounds that any animal or thing has been removed from, moved within or taken into a control area in contravention of a regulation made under subsection (3), the inspector or officer may, whether or not the animal or thing is seized, (a) return it to or remove it from the control area, or move it to any other place; or (b) require its owner or the person having the possession, care or control of it to return it to or remove it from the control area, or move it to any other place…”

Brucellosis, a notifiable disease under Canada’s Health of Animals Act, was diagnosed in harp seals, hooded seals, grey seals and harbour seals in Atlantic Canada in the late 1990’s according to reports published in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases. Brucella is known to be easily transmitted between animals and to be maintained in populations of social animals that tend to congregate in herds, like cattle, goats, sheep, bison, caribou and seals. The scientific literature also subsequently reported cases of the seal strain of Brucella causing serious human illness. Further, it has been demonstrated experimentally that the seal strain of brucellosis is dangerous to cattle.

Did these scientific discoveries and publications cause any Canadian veterinarian or Canadian person who analyses animal specimens to form a legally reportable ‘suspicion’ in their mind that Atlantic seals might be ‘affected’ by brucellosis? Did any person subsequently report such a suspicion to a veterinary inspector, and was any seal-occupied area subsequently declared to be an ‘infected place’ or a ‘control area’? Was a five kilometre zone around seals declared to be a brucellosis control area and were people prohibited from removing animals or animal parts from the area? Obviously, none of these infection control measures were taken, and I do not know if any Canadian veterinary inspector ever received a report of a suspicion of brucellosis in the seals. It seems that such a report may have been received without CFIA going on to take steps to control the spread of the disease, as this is within their discretion.

4. Focus on brucellosis in seals: how much do we know, and how has Canada handled this information? Major questions: why has the Canadian government provided public education and food safety programs for hunters and consumers of marine mammals in the Arctic region only, when evidence of seal disease was found in the Arctic and Atlantic Regions simultaneously and the bulk of seals killed for human consumption are hunted and processed in the Atlantic Region? In their letters of response to me, did Health Canada suggest that seal Brucella is not bacteria of public health importance in Atlantic Canada…while CFIA and the Canadian Cooperative Wildlife Health Centre (CCWHC) are suggesting to northern people that seal Brucella is bacteria of public health importance in the Canadian Arctic?

Consider the following series of information items with regards to zoonotic diseases in seals, brucellosis in particular:

“Brucellosis in Ringed Seals and Harp Seals from Canada,” a scientific article published in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases 36(3) 2000, pp 595-598 by Lorry Forbes (CFIA), Ole Nielsen (DFO), Lena Measures (DFO) and Darla Ewalt (US Dept of Agriculture).

The (freely available to the public) title and article abstract concisely summarize the findings: “This is the first confirmed report of brucellosis in marine mammals from Canada, and the first report of this organism in ringed and harp seals.” This is an unambiguous report of brucellosis in a commercially used species, the harp seal. Regarding the potential for humans contracting and becoming ill with seal brucellosis, the authors wrote “…appropriate precautions should be taken under conditions of potential exposure until more data are available,” although their first impression was that their findings did not represent a significant health threat. Did these scientists formally report to veterinary inspectors at CFIA their ‘suspicion’ that seals were affected by ‘brucellosis’? (Because the reporting requirement under the Health of Animals Act does not identify or exempt any particular strains of brucellosis.)

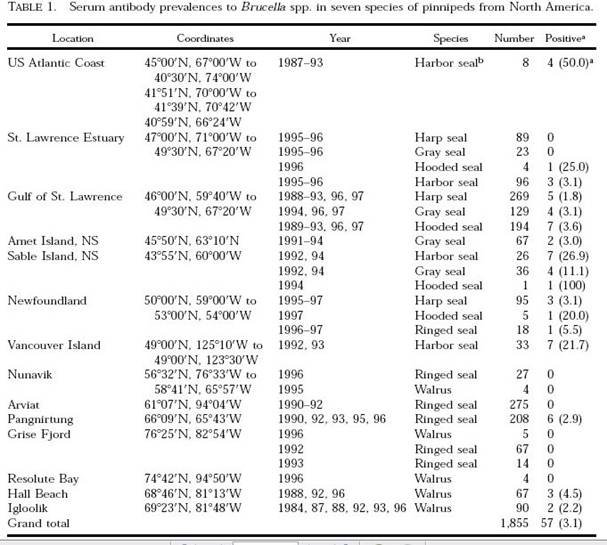

“Serologic Survey of Brucella spp. Antibodies in some Marine Mammals of North America,” published in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases 37(1) 2001, pp 89-100 by Ole Nielsen (DFO), Robert Stewart (DFO), Klaus Nielsen (CFIA), Lena Measures (DFO) and Padraig Duigan (New Zealand). ( )

The title and article abstract in this instance do not identify which species of marine mammals were studied, although the abstract indicates that both cetaceans and pinnipeds (meaning whales and seals) tested positive for Brucella antobodies. ‘North America’ in the title does not reveal how overwhelmingly Canadian the study was. A total of 1855 seals were tested, 1847 from Canada plus 8 stranded harbour seals from the US Atlantic Coast. Of 597 whales tested, 578 were from Canada, while 19 were pilot whales that stranded along the US Atlantic coast. In this study, therefore, 2425 Canadian samples were tested, plus 27 samples from the US Atlantic Coast (i.e. 99% Canadian animals)…no marine mammals were sampled from Alaska, none from the US Pacific Coast and none from Mexico…why then did the authors identify the study area as ‘North America?’ Why, too, did they not write ‘seals and whales’ instead of ‘some marine mammals’ in their title, when no polar bears, otters, mink or manatees were included in their survey?

Regarding human health implications, the authors wrote “The zoonotic potential of the newly discovered marine mammal Brucella spp. strains is unknown but given that most of the known strains are human pathogens, it would be prudent to regard the marine mammal strains as such until proven otherwise…exposure to Brucella organisms could occur through dressing carcasses or by consuming raw meat…it is likely that there is risk to people who come in contact with marine mammals that have stranded and are likely to be ill, or those who consume hunted animals. Caution and good hygienic practices are advised in either situation.” Did the authors at this time report to veterinary inspectors at CFIA their suspicion that seals were affected by brucellosis?

The findings of the Brucella serologic survey with regards to seals was summarized in the table below:

If these results are considered in terms of Arctic (north of 60 plus Nunavik) versus sub-Arctic locations of the seals that were tested, it can be seen that 11/761 Arctic seals tested positive (1.44%) while 50/1093 sub-Arctic seals tested positive (4.57%). (Note that the table contains an error in the ‘grand total’ of positive findings. 57 is entered, but this is the total only of Canadian positives, while the actual grand total is 61 after the US data is added. Does this error indicate that the American data was added as an afterthought in this study?) The results for whales were summarized similarly, and the findings were similar in that 5.34% of Arctic whales and 7.4% of sub-Arctic whales tested positive for antibodies to Brucella.

The percentage of positive findings was higher below the Arctic for both seals and whales. The positive finding was also more consistent and widespread below the Arctic. Of 7 different Arctic locations tested, 3 showed seals testing positive for Brucella exposure, while all seals tested in the other 4 northern locations were negative, suggesting a relatively spotty distribution of the infection in the north. In contrast, positive results were found in seals in every one of the 7 locations tested below the Arctic. Why, then, did these authors and the Canadian government go on to address the potential human health threat of contracting brucellosis from marine mammals by framing it only as an Arctic food safety issue, especially given that greater numbers of marine mammals are killed and consumed in Canada’s Atlantic sub-Arctic region?

Canadian Cooperative Wildlife Health Centre (CCWHC) Newsletter 6 - 1. A news item in this (freely available to the public) newsletter was titled “Brucellosis in Marine Mammals of Arctic Canada,” written by Ole Nielsen (DFO), Lorry Forbes (CFIA), and Klaus Nielsen (CFIA).

The news article summarized the recent findings of brucellosis in Arctic seals and whales, including some results from the serologic survey reported in the JWD in 2001, above. The authors explained the reason for their study: “Since marine mammals constitute a considerable portion of the diet of northern Canadians and several species of terrestrial Brucella are known to be pathogenic for humans, the presence of brucellosis in marine mammals may pose a food safety risk for northern Canadians. Therefore, work was initiated by personnel from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, in conjunction with personnel with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, to determine if marine mammal Brucella are present in the Canadian Arctic.”

A paragraph was included at the end of this ‘Arctic’ news item describing some findings in seals below the Arctic: “Antibodies to Brucella sp. also have been found in harbour seals (Phoca vitulina) in southern Canada and the adjacent USA. Seven of 33 seals from Vancouver Island (1992-93), 4 of 8 from the US east coast (1987-93), 3 of 96 from the St. Lawrence estuary (1995-96) and 7 of 26 from Sable Island (1992, 1994) were positive. From these data, the overall prevalence of sero-positive harbour seals was 21 of 163 or 13%.”

The numbers quoted for the harbour seals are the very same numbers that appear in the table above, seemingly cherry-picked from the larger survey. Harbour seals are small seals that are not hunted, butchered, marketed or consumed commercially. Why did these scientists not report in the CCWHC newsletter that they had also obtained positive brucellosis findings in Atlantic hooded seals, harp seals and grey seals, all species that are hunted commercially for human consumption? Why did they not identify a similar potential disease threat for Atlantic region sealers and consumers of seal products from Atlantic Canada, and why was the CCWHC’s subsequent initiative dealing with zoonotic risks from seals framed only as an Arctic issue? Might political pressure have influenced the handling of scientific information revealing that commercially harvested seals are affected by a reportable disease?

“Diseases and Parasites of Marine Mammals of the Eastern Arctic,” a Field Guide published by the CCWHC in 2003. Illustrated guide for hunters, showing visible signs of diseases known to affect marine mammals. Included is basic food safety advice describing various signs that indicate a carcass should not be eaten by people or fed to dogs. Hunters are instructed on how to collect tissue samples to send to scientists when they see certain abnormalities in animals. They are also advised of zoonotic threats from ‘rabies, trichinellosis, mycoplasma and brucellosis.’

Did the DFO and the CFIA go on to initiate any similar work in Atlantic Canada to “determine if marine mammal Brucella are present” or to educate marine mammal hunters and consumers to avoid potential food safety hazards that might arise from the commercial hunt for harp seals, hooded seals and grey seals? If they did, I have not found any record of this work.

“Human neurobrucellosis with intracerebral granuloma caused by a marine mammal Brucella spp.” April 2003, reported by medical doctors in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, two cases of severe human brucellosis caused by the strain of Brucella that is found in seals.

“Evidence of Brucella sp. infection in marine mammals stranded along the coast of southern New England,” published in the Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine September 2003, 34(3) 256-61, by DR Ewalt, JL Dunn and others. Positive cultures for Brucella were reported from harbour seals and harp seals stranded in Connecticut and Rhode Island. Harp seals in this area are stragglers that have strayed south from the Atlantic Canadian herd, a seal herd that is hunted commercially on large scale. (The legal reporting requirement under Canada’s Health of Animals Act that binds veterinarians and scientists in Canada does not likely apply to those working in other countries.)

“Marine mammal brucellosis in Canada, 1995-2004” A presentation on this topic was made at a conference held in the Ukraine, by O. Nielsen (DFO), K. Nielsen (CFIA), D. Ewalt (US Dept of Agriculture), S. Raverty (BC Animal Health), R. Stewart (DFO) and B. Dunn (DFO).

“Brucellosis is a severe zoonotic disease and there are two reports of disease in humans attributable to marine mammal Brucella infection…A marine mammal sampling program of hunter-killed (and presumably healthy animals) and post mortem examination of beach-cast carcasses, presumably unhealthy, marine mammals has been on going in Arctic and Pacific regions of Canada since the early 1980’s and late 1990’s respectively…”

Does this indicate that as of 2004 DFO and CFIA had initiated no marine mammal sampling program in the part of Canada with the greatest number of hunter-killed marine mammals, the Atlantic region? If not, why not?

“Isolates were recovered from animals in Hudson Bay, Amundsen Gulf, the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Baffin Bay, and Davis Strait…”

The Gulf of St. Lawrence isolate refers to the harp seal isolate reported in the DFO/CFIA scientists’ first report, “Brucellosis in Ringed seals and harp seals from Canada.” That seal was not found in an ‘Arctic and Pacific’ sampling program! Were no further Brucella isolation attempts made from seals in Atlantic Canada, despite the relatively high prevalence of positive serologic tests found in the region, the commercial use of these seals for human consumption, and the resulting relatively easy access to large numbers of hunter-killed carcasses? If not, why not?

“Marine mammals and "wildlife rehabilitation" programs” DFO Science research document, 2004 by Lena Measures (DFO) This paper recommended that “wildlife rehabilitation” of marine mammals not be permitted by DFO, and that current initiatives be discontinued. This was written in a climate of virtually no (published) knowledge about the disease status of Atlantic seals. A sick harbour seal pup died during a rehabilitation attempt by the sole licensed provider of this service in Nova Scotia. The rehabilitation provider sought a veterinary post-mortem exam of the dead seal, and was told the carcass should not be sent to the Atlantic Veterinary College for diagnosis, but to the Nova Scotia Agricultural College instead. That was done, but follow-up enquiries elicited only the message that the dead seal had been ‘lost.” Ergo, no seal disease diagnosis. Coincidence?

CBC Radio News North Transcript, August 8, 2001, Iqalawit:

DRYSDALE: A disease called brucellosis has turned up in

marine mammals throughout the Canadian Arctic. Until recently, the bacteria that

causes the illness was only thought to occur in land animals like caribou and

cattle. They can pass the disease on to humans, causing high fevers, headaches

and flu-like symptoms. Now, federal scientists are trying to find out whether

marine brucellosis might also pose a risk to humans. Patricia Bell reports:

BELL: The Department of Fisheries and Oceans has now isolated about nine cases

of marine brucellosis in ring seals, harp seals and a beluga whale in the

Canadian Arctic. Ole Nielsen says it’s probably affecting narwhal and walrus as

well. Nielsen is a marine mammal disease specialist with the department.

NIELSEN: The fact we’ve got isolations from the eastern Arctic, from

Chesterfield Inlet in Hudson’s Bay and all the way to Holme in the western

Arctic, I worry about findings like this.

BELL: Nielsen says marine brucellosis causes mainly reproductive problems in the

animals it infects, but he doesn’t know if it can cause disease in humans.

That’s something he and Health Canada hope to find out soon. Dr. Harvey Artsob

is with Health Canada’s national microbiology laboratory.

ARTSOB: We are certainly at the stage of saying we think this is a legitimate

problem and we are now in the planning stage to see whether we can in fact

undertake the study by getting some blood samples from individuals who handle

marine mammals up north.

BELL: Artsob says determining if marine brucellosis is a risk to people in the

Arctic has become one of Health Canada’s priorities.

BELL: Patricia Bell, CBC News, Iqalawit.

“Seroprevalence of Zoonoses in Nunavik: Surveillance and risk factor assessment” In 2004, led by public health professionals in Quebec, blood was collected from over 900 Inuit to test for exposure to a range of zoonoses, including those known to be carried by marine mammals. Report not located yet.

“Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in Canadian Pinnipeds,” in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases 40(2), 2004, pp. 294-300, by Lena Measures (DFO), J. P. Dubey (US Dept of Agriculture) P. Labelle (CCWHC) and D. Martineau (CCWHC). Positive findings of exposure to this parasite were reported from the “east coast of Canada” in grey seals, hooded seals and harbour seals. Harp seals that were tested were found to be negative. The authors concluded: “Toxoplasmosis is a serious zoonosis, and finding Canadian marine mammals exposed to T. gondii is of concern to native peoples, such as Inuit, to sealers on the east coast of Canada who consume marine mammals, or to domestic or international seal meat markets. Recent studies indicate that human health can be at risk.”

The biggest risk from toxoplasmosis is to people with weakened immune systems and to unborn babies, as severe birth defects can result if the mother becomes infected with this parasite during pregnancy. This is included here to remind readers that this story, and the argument that seals cannot be safely processed as fish, is not all or only about brucellosis.

There is no legal reporting requirement for toxoplasmosis under the Health of Animals Act, yet it seems the CFIA might reasonably be expected to act on this information when they provide food safety guidelines to the processors of Nova Scotia grey seals…even if the CFIA still thinks seals are ‘fish,’ the presence of toxoplasmosis would render seals ‘unwholesome’ under the Fish Inspection Act.

“A comparison of four serologic assays in screening for Brucella exposure in Hawaiian monk seals,” in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases 2005, 41(1) pp 126-133 by O. Nielsen (DFO), K. Nielsen (CFIA), R. Braun (Hawaii) and L. Kelly (CFIA). “A survey for Brucella spp. antibodies was undertaken on 164 serum samples from 144 Hawaiian monk seals (Monachus schauinslandi) from the northwestern Hawaiian Islands collected between 1995 and 2002…” In which Canadian scientists report doing surveillance testing for brucellosis on American seals. Have these researchers also been employed doing similar testing on seals from Atlantic Canada? If so, where are those results reported?

“Hematology and serum chemistry of harp (Phoca groenlandica) and hooded seals (Cystopora cristata) during the breeding season, in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Canada,” in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases 42(1), 2006, pp. 115-132, by France Boily (DFO, a veterinarian), Sandra Beaudoin (veterinary faculty at University of Montreal) and Lena Measures (DFO). Harp seal mother-pup pairs were killed and adult hooded seals were live-captured to obtain blood samples that were analyzed by these scientists for blood cell count and blood chemistry values. What they reported in this paper was the normal values of these blood parameters for these seals, and they reported no testing and no evidence of any “wildlife diseases” at all.

However, did these scientists also test the seals’ blood for brucellosis and other zoonoses, and did they collect seal tissues besides blood for disease testing? From the harp seals that were killed, did the researchers also take spleens, livers, lymph nodes, etc. so that they could conduct a full disease screen profile on the animals? All things considered, it is hard to imagine that this was not done. If these researchers found evidence of brucellosis in seals, did they report this finding to a veterinary inspector at the CFIA as they were obliged to do under Canada’s Health of Animals Act? Or did they send seal tissues to someone else, inside or outside Canada, to be checked for brucellosis?

US Federal Register, January 30, 2004 – Issuance of permit: “Notice is hereby given that Darla Rae Ewalt, Principal Investigator, Diagnostic Bacteriology Laboratory, National Veterinary Services Laboratories, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, US Department of Agriculture, 1800 Dayton Road, Ames, IA 50010, has been issued a permit to import/export marine mammal specimens from Canada for purposes of scientific research…Supplementary information from October 9, 2003: “Darla Ewalt (File no. 1038-1693/PRT-064776) requests authorization to receive from Canada tissue samples taken from legally harvested beluga whales, narwhals, walrus and ringed seals. Tissues to be imported include blood, lymph nodes, lungs and reproductive organs. These samples will be utilized in brucellosis research investigating the presence of Brucella in subsistence harvested marine mammals. The applicant is requesting a five year permit.”

Darla Ewalt needs a permit to import marine mammal tissues from Canada into the US because of the import ban imposed by the American Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972. Since she had already been involved in testing harp seals for brucellosis, it seems curious that Ms. Ewalt did not include this species in her permit application. If Ms. Ewalt did happen to diagnose brucellosis in seals harvested commercially in Canada, she would presumably not be bound to file a report under Canada’s Health of Animals Act. However, if she sent her report to Canadian scientists, would they then be obliged to report her finding to the CFIA?

Why do we have DFO/CFIA scientists testing for brucellosis in American seals while Canadian seal samples are being sent to the US to be tested for the same disease?

“International Polar Year Proposal for 2007-2008: Brucella-infections in seals: Zoonotic potential of marine Brucella sp. and the combined effect of infection and exposure to persistent organic pollutants.” This project is proposed and will be led by the Norwegian School of Veterinary Science. However, DFO employees Ole Nielsen and Garry Stenson are listed as collaborators, and the list of planned study locations includes Newfoundland. Therefore, it seems commercially harvested seal herds in Atlantic Canada might soon be tested for brucellosis in another foreign-initiated study?

DFO Seal Forum 2005 – report from the Independent Veterinarians' Working Group (IVWG)

Formal veterinary advice from the IVWG was presented on day 1 of DFO’s November 2005 seal forum, and the recommendations were largely limited to ‘humane slaughter’ considerations. However, at the end of the second day, IVWG member and American veterinarian, Lawrence Dunn, returned to the podium and gave a brief presentation to the forum on seal brucellosis, explaining that he had diagnosed this bacterial disease in some stranded seals in New England. My recollection of his talk does not include Dr. Dunn saying that he had diagnosed brucellosis specifically in ‘harp seals’ in New England, seals that had strayed south from the Canadian herd, and I therefore assumed he was telling us he’d found brucellosis in harbour seals and grey seals. Dr. Dunn then asked the sealers at the forum to let him test their blood for Brucella antibodies. This item was not included on the formal agenda, and it took place on the second day of the forum, after the Canadian veterinarians who had participated in the IVWG had apparently left the meeting.

In the Canadian Arctic, marine mammals and humans both have been openly studied to determine the extent and seriousness of marine brucellosis and other zoonoses. First, get a handle on what fraction of wild animal herds are carrying a pathogen, and then find out how many people have contracted the infection and whether or not it has made them ill. This is absolutely above-board, and as far as brucellosis in food animals is concerned, this approach is pretty much in line with what the FAO/WHO recommends to developing countries. But that is not what is happening in Atlantic Canada, where the approach seems best described as strategic non-surveillance of wildlife diseases in commercially used seals. Does the Canadian government have an aversion to acquiring this type of information, perhaps an especially strong aversion to veterinary diagnosis of infectious diseases in Atlantic seals? Is that why it seems only a few clues will be quietly uncovered by foreign investigators rather than having this matter examined by open scientific enquiry inside Canada?

Why has Canada been so reluctant to study diseases in commercially harvested seals in Atlantic Canada? The real reason may be that commercial marketing opportunities stand to be lost if this type of wildlife disease information is made public, a reason that was verbalized ten years ago in Alaska...

“Wildlife Diseases: implications for resource harvesting and utilization in the Northwest Territories, Canada,” a presentation made at the 1996 Wildlife Diseases Association annual conference by Brett T. Elkin, Department of Renewable Resources, Government of the Northwest Territories:

“A number of enzootic diseases and parasites occur in big game species found in the arctic and subarctic regions of northern Canada. These can have a number of implications for the subsistence, sport and commercial harvesting of wildlife. In the Northwest Territories, the sustainable harvesting of wildlife resources is very important to the economy and lifestyles of northern residents…The skills and experience acquired by subsistence harvesters are important in recognizing diseases and parasites in wildlife, and their implications for food quality and safety. Hunters generally select against obviously diseased animals in order to avoid condemnation of the carcass and loss of hunting effort. Zoonotic diseases such as brucellosis in caribou can have direct human health implications for resource harvesters, and may influence carcass utilization and harvesting patterns…It is important to recognize that both real and perceived changes to the health of wildlife can influence utilization of an individual animal, and possibly influence future harvesting activities. Public education on wildlife diseases and parasites is important, but must take into account the broader health, economic and social consequences of any advice that may influence harvesting or consumption patterns.”

Mr. Elkin seems to have been worried, in part, that big game hunters (for caribou?) might not continue to bring their business to the NWT if too much information was made public about diseases in the animals. He may have a point, especially if the native hunters do in fact know how to avoid the risky animals and if “condemnation of the carcass” ultimately stands to prevent human consumption of any diseased hunter-killed animals. It may be unfair of me even to include Mr. Elkin’s comments here, because nothing has led me to think that hunters in the Northwest Territories ever avoid condemnation of diseased wild mammal carcasses by any strategy, let alone by pretending they are fish instead of meat, the routine used by seal processors in Atlantic Canada. Public education on seal diseases in Atlantic Canada, and on the absence of any screening process to ensure that diseased seal carcasses are condemned as inedible, this could definitely “influence harvesting or consumption patterns”…this could potentially end the commercial seal hunt.

In contrast, consider public education on marine mammal diseases and parasites in the United States. A 2004 report prepared for the US Marine Mammal Commission was titled “Assessment of the risk of zoonotic disease transmission to marine mammal workers and the public: survey of occupational risks”. The findings were summarized in a two-page health and safety brochure, included in the report. An excerpt:

“Exposure to marine mammals can mean exposure to the diseases they carry…Several dangerous infections were reported by marine mammal workers, including tuberculosis, leptospirosis and brucellosis…Care must be taken to avoid all possible routes of exposure to marine mammal infections. Although bites and contact with existing wounds are the most common routes, infections can occur through your mouth, eyes, respiratory system and skin…If you develop an illness or other condition that could be caused by exposure, be sure to tell your physician that you work with marine mammals.”

What would happen if someone caught seal brucellosis and their physician did not consider it as a possible diagnosis? Possibly, a scenario might unfold along the lines of a story that was reported in a Nova Scotia newspaper early in 2006 (excerpts below from the Halifax Chronicle Herald):

“Family thankful cancer diagnosis incorrect

(A mother’s) life became a nightmare in January when her daughter was diagnosed with cancer – but there’s a very happy ending. The 17-year-old girl had been miserably ill since October, and doctors couldn’t find anything wrong with her. She was losing weight and had a severe sore throat, and her lymph nodes were badly swollen…”It hurt her so bad to swallow that by January she had lost 30 pounds and we were taking her to emergency all the time. She would just lie on the couch crying saying, ‘I know I am dying, Mom.’”…(The girl) was sent for testing at the South Shore Regional Hospital in Bridgewater and the Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre in Halifax, her mother said, and later had surgery to remove a large lymph node from the back of her neck. Analysis led doctors on the South Shore and in Halifax to diagnose Hodgkin’s lymphoma…”When we were told, it was absolutely devastating.”…Doctors told the teen that her chances were very good, but she would have to undergo 16 rounds of chemotherapy and six weeks of radiation to rid her body of the disease…Her treatment was set to begin in March…but the day before she was to make the trip to Halifax the family got another call. A pathologist who was looking over the case questioned the diagnosis and asked that the lymph node be sent for further tests. “I don’t know who that doctor was or where the lymph node went, but when the results came back negative, they passed her case on to an infectious disease doctor and we found out that she had a severe bacterial infection – not cancer,” her mother said…”I am no doctor and I know that mistakes happen, but if she had had the chemo it would have depleted her immune system, and she could have died from the infection.” No treatment was required for the infection as doctors told the family it would simply run its course…”

This story is presented here only to give an idea of what might happen if Canadians contract brucellosis and their doctors do not think to test for the disease, because the diagnosis of brucellosis can be confused with cancer of the lymph nodes. I do not claim that the bacteria that caused this girl’s illness was Brucella, because I do not know what it was, nor do I know any more about this case than what was reported in the newspaper. The type of bacteria was not identified in the story, but it seems the girl’s symptoms resolved spontaneously after several months of severe illness. Brucellosis has long been known as “undulant fever” in parts of the world where it is commonly found, because the symptoms in humans can wax and wane for months at a time. Some people fight off a brucellosis infection after an initial illness, while others, if untreated, go on to live with recurrent chronic symptoms for many years.

If medical doctors do not look for brucellosis, they will not find it, and most Canadian physicians have never seen this disease because our meat supply has been ‘brucellosis-free’ for years. Physicians working in the Canadian Arctic have seen human brucellosis, however, because several cases yearly are diagnosed in people in the north (presumably contracted from caribou and reindeer).

Someone else has previously requested information on brucellosis in Canadian harp seals through the federal Access to Information Act, but I cannot determine who made this request or what information they might have received.

5. Wildlife Disease Surveillance in Canada

Canada has recently implemented two new wildlife disease monitoring programs, the “National Aquatic Animal Health Program” (NAAHP) and “Canada's National Wildlife Disease Strategy”. However, I have found no indication to date that either of these initiatives has led to any open surveillance of the infectious disease status of seals in Atlantic Canada. A DFO paper titled “Aquatic Monitoring in Canada: a report from the DFO Science Monitoring Implementation Team” explains with regards to the NAAHP: “This program is tightly focused on a specific set of listed, infectious diseases of aquatic animals that impact international trade in seafood products or are expected to cause harm if inadvertently introduced or moved within Canada.” While it seems at first glance that the new NAAHP (with $59 million in new federal funding to be used by DFO and CFIA) should lead to monitoring of seal diseases because they could “impact international trade in seafood,” the literature on the NAAHP indicates that the program is focused only on diseases of fish raised in aquaculture.

FAQ are answered about the NAAHP on the CFIA website ( http://www.inspection.gc.ca/english/anima/aqua/queste.shtml ), including:

|

Q7 |

From what legislation does the NAAHP draw its authority? |

|

A7 |

|

|

Q8 |

What role do the provinces and industry play in the NAAHP? |

|

A8 |

|

|

Q9 |

Were Canadians at risk before the NAAHP? Are there aquatic diseases that pose a human health or food safety risk? |

|

A9 |

|

|

Q10 |

What are reportable diseases? |

|

A10 |

|

The answer to Q9 above seems to reveal that the CFIA limits the meaning of ‘aquatic diseases’ to diseases affecting cold blooded ‘aquatic resources’. The answer “No…none of these diseases is known to pose a threat to human health” in response to the question “Are there aquatic diseases that pose a human health of food safety risk?” seems to reveal the same assumption that realistically lay beneath the creation of the Fish Inspection Regulations, the belief that people cannot catch fish diseases and that the involvement of veterinarians and meat safety protocols is therefore not necessary in fish processing. Why, then, does the CFIA insist that “seals are classified as fish” for the purpose of food processing, when even their own scientists have warned that seal diseases can potentially threaten human health.

In Canada, therefore, seals are omitted from the NAAHP because they are not fish but mammals, while seals are simultaneously exempted from the Meat Inspection Regulations because they are marine mammals, and a creative misinterpretation of the Fish Inspection Act is then used to argue that these marine mammals can legally be processed as fish. So seal diseases disappear in a fog of confusion? How long can this farce go on?

Will one of the Atlantic Provinces and naïve members of the fishing industry soon innocently ask DFO and CFIA to include seal disease monitoring in the NAAHP?

6. What does the fishing industry think? (Marketing seal products for human consumption has been difficult, and the industry does not seem to understand why I have tried to raise a food safety concern about their seal products, or why government departments insist on calling seals ‘fish’.)

Establishing markets for the newer ‘full use’ range of seal products, and dealing with government rules, has led to frustration and confusion in the industry. In testimony given to the Federal Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans in 2003, Tina Fagan (Canadian Sealers Association) touched on the problems (http://cmte.parl.gc.ca/cmte/committeepublication.aspx?sourceid=33790 at 1555h):

“Sometimes I think that with friends like government, we don't need enemies. When we started trying to market our salami and pepperoni, excellent products that were market-tested across Canada and we had potential markets for, Health Canada said, “Hold it just a minute. You can't do that.” Why not? “Because seal is a fish.” No, it's not, and any Newfoundlander can tell you seal is not fish. “Well, it comes from the sea, and Fisheries and Oceans governs it, so therefore we treat it as fish.” If it's fish, you see, you can't add certain additives to give your product shelf life. “Now, if you want to sell it out of the country, you have our blessings. We will give you all the documentation you need to sell it out of the country.”

So I went to China with Mr. Efford. We weren't specifically marketing seal meat, but if I'm marketing to you, and you're in one of these countries, and I'm trying to sell you this product, if you're a smart fellow one of your first questions to me is going to be, “How much of this is used domestically?” None. “Well, why not?” Because Health Canada won't let us. “Then screw you. Why would we want to take what you're dumping?”

That situation has been resolved, but it took certainly eight years of my time, and time before that, and the time of Mr. Efford, when he was the minister here, to get that resolved.

So we have Fisheries and Oceans, which governs the enforcement of the harvest. We have Health Canada, which has to come in on issues of this nature, and that's fine as long as they do it properly. We have Agriculture Canada, who reports seal meat as meat. We have no problem there.”

It is not clear to me just what Mr. Efford got resolved; might he have found the way to open the domestic and export markets for seal oil capsules? Was political pressure applied to the CFIA and Health Canada? Regardless, Ms. Fagan is clear that sealers do not accept that “seal is a fish.” They think that seal meat is meat…

On May 30, 2006 the same government committee heard testimony from Denny Morrow, representing the fishing industry in Nova Scotia regarding their desire to increase the commercial use of grey seals ( http://cmte.parl.gc.ca/Content/HOC/Committee/391/FOPO/Evidence/EV2231930/FOPOEV04-E.PDF ). A question regarding seal diseases was asked by one of the MP’s (page 17 in the transcript):

"Mr. Peter

Stoffer:… “You

probably read in the

Chronicle

Herald

newspaper last week an article by a woman named Debbie Mackenzie, who is from

Mr. Keddy's riding, I believe. She was talking about diseases that seals carry,

like brucellosis, tuberculosis, and so on. She made the allegation that CFIA or

DFO is not doing a complete health analysis of the seal meat when it is being

exported overseas.

I am just wondering if you could comment on that particular article, because I

have not heard a countervailing argument to what she has stated about the

handling of the meat, and the concern that fishermen should have for handling

seal meat, and also about the various diseases that seals do carry, if indeed

they carry them at all.

●(1050)

Mr.

Denny Morrow:

Thank you, Mr.

Stoffer. … With regard to the article in the

Chronicle

Herald,